The Image Makers 4

Von had always had a love affair with

horses; I've not come across a single mention of Rockwell ever

having been on one, John Ford (who claimed to have once "been a

cowboy and punched cows for awhile," sounded as unconvincing as the

few existing photos of him on horseback. One description was "he

looked like a sack of walnuts." But he didn't need to know

how to ride. In his medium the horse served as Metaphor, source

of excitement, and powerful image.

When they were both founding members for The

Famous Artist's School, Norman spent an afternoon with Von. Von had

convinced himself that with his method of "comparative anatomy" that

anyone could paint horses in motion as he did. I don't think he

convinced Norman! During his many years with the "slicks”, Von

really had no imitators. The closest thing to it was to come later,

when after the magazines died out most of Westport's illustrators

actually moved west and became "western artists."

Russell and Remington also were both bound up

in the mystique of the horse. Charlie maintained it was impossible

for someone to paint a horse if he was not a rider -- a student of

the horse, and my father believed that too.

Von's First Image

Indeed, his very selfhood had to do with a

chalk drawing of horse he had drawn in class, and his teacher

admired it, so she took him from classroom to classroom showing it

to the entire school. "Before that I was nobody. Then all of a

sudden, I was somebody… I became the kid who could draw horses. I

could never repay that teacher, but she gave me an identity. And I

knew I wanted to be an artist after that."

Another one of his favorite stories was about

two fire horses that were running loose in the streets of Alameda

following the San Francisco earthquake of 1906…"I cried when they

took my horses away. Those were the first horses I ever thought

I owned."

Soon after Von and Reb bought their house on

Deadman's Brook in Westport, a stable was added and two horses and a

pony were in residence. My mother was a fine rider, and my older

brother and I learned at an early age. Von still wore a Stetson and

was determined not to forsake his claim as a "westerner".

Reb and Von

Although his knowledge of the horse was already

encyclopedic, he would still use this little "herd" to make

occasional sketches, either in the barn or out in the direct

sunlight. He did the same with water flowing in Deadman's Brook.

Everything had an "anatomy": trees, the earth, even clouds, I not

only had the opportunity as a child to see him create his

illustrations in the studio, I was invited on many of these

sketching expeditions.

Having been introduced to out-of-door sketching

(oil painting, actually) at an early age, I can attest that

something happens in the process that is almost mystical. The

experience of being outdoors as opposed to recreating a color

photograph of an "outdoor scene" is key to the process.

We did our outdoor painting on 8" by 10" pieces

of illustration board. They were painted directly in oil, and the

board was not sized in any way. Just the pristine white. Because the

total area is so small, no pencil sketch was deemed necessary. You

just squeezed out the oil paint on a small wooden hand-held palette,

put the cardboard on your easel, looked at your scene and started.

Turpentine in a little metal cup hitched to your palette, served as

your medium.

The beauty of this

process is that, unlike a color photograph which takes less than a

second, that for the half, three quarter, or hardly more than an

hour, your subject matter is in constant motion. You are

playing a game of tag with the light, the shadows, the clouds...you

become aware of the top light, the reflection of the sky… the bushes

and the distant trees might change in softer ways, might go from

bluish hues to golden. Harsher contours change in more dramatic

ways. The sky is the most dramatic actor of all. You are always

playing catch up...and you are in the vital process of learning.

Perhaps you are learning about change, about Nature.

Maybe...about life?

How To Draw Cowboys And Indians

In May of 1948 Von was getting all these

western serials to do for the Post (John Ford was making

movies from some of them) and I had just gotten my driver's license.

It seemed like a good time to take a real sketching trip, camp out

and paint Monument Valley (where Ford was shooting the movies) and

then go south to Apache country (where James Warner Bellah was

locating his short stories.)

After sketching in Taos, where Von had painted

briefly in the twenties, we headed for Monument Valley. We stayed at

Harry Goulding's Trading Post, and it is a great pleasure to say,

after reading Ron Davis's biography, that Harry and his wife "Mike"

had no horror stories to tell about "Mr. John" and that he (Mr.

John) had no complaints about them. Of course, they weren't

obliged to act. Also, Ford's filmic safaris were of vast

benefit to the Navajo tribe during lean times.

Like John Wayne, Harry Goulding sure as hell

knew about Von's paintings for The Saturday Evening Post, and

was delighted to see Von there with his son, actually sketching his

beloved valley. It was fascinating to hear the two of them talk

about the early days, their involvement with Indians, (Harry

spoke Navajo) and Von's memorable trip on horseback with a

Navajo guide in the late teens.

After three or four days sketching in the

stately Valley, we drove south, where the country (“Bellah Country")

got meaner and the desert more inhospitable, and while Von tended to

relegate Remington to the ranks of the Eastern Western

painters, "Bud" claims my admiration for his description of the

country that unfolded before us. (Indeed, though he was never near

Monument Valley, he was with General Crook during the period

Bellah fictionalized): “Let anyone who wonders why the troops do not

catch Geronimo, but travel through a part of Arizona and Sonora,

then he will wonder that they even try. Let him see the desert

wastes of sand devoid of even grass, bristling with cactus...let the

sun pour down white hot upon the blistering sand about his feet and

it will be plainer."

When we reached our destination, we discovered

that the “old" Fort Grant no longer existed. In fact, as I was to

learn years later, in the words of General Crook's aide, John G.

Bourke, this “most forlorn parody of a military garrison...there

would be very little use in attempting to describe Old Fort Grant,

Arizona, partly because there was really no fort to describe..."

Such was the actual fort from which Bellah's

fictional cavalrymen rode forth to smite the fiends incarnate, the

hellish Apache led by the arch-enemy-Geronimo. There are relatively

few photographs of Apaches of the period, but Von searched them out.

They wore white man shirts, vests and the mid-calf leather legging

with the turned-up toe.

As for US Cavalry uniforms and equipment, Von

tended to look to Remington because he "was there." This worked okay

up to a point, but to my mind his biggest gaffe was making the issue

dark blue coats (“blouses") too "powder blue", and the "sky-blue

kersey" pants too green. While Remington might have approached that

color scheme in a few later paintings in a specific light, it just "ain't

right."

Ford didn't have to worry about shades or

color. His cavalry uniforms came from the costume department, and

they were usually pretty good. His main concern was that they look

worn, and he was right, because they usually didn't. It must

be remembered that Harold von Schmidt was considered a paragon of

research and authenticity from the thirties to the sixties. In

Hollywood, a make-up man's idea of "going through hell on a

battlefield" was to tear the guy's shirt diagonally, just above the

elbow, and smudge his cheekbone ever-so-artfully with burnt cork.

All this was well before the reenactment groups with their accuracy

fetishes.

Von knew "raggedy." His soul was

raggedy. Like John Ford, (and unlike James Warner Bellah,) he

instinctively sided with the underdog: with the Indians, the

immigrants, with "the raggedy kids from the orphanage."

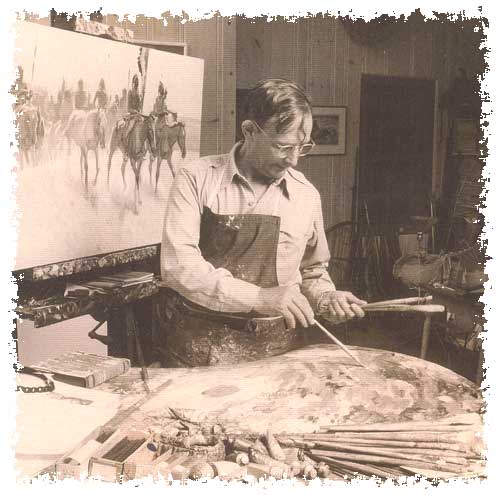

Harold painting what would

appear in James W. Bellah's "The Last Fight" Saturday Evening Post,

October 16, 1948

Custer Shows Himself

When, in the late sixties, I decided to tackle

a monumental painting of the Custer fight on the Little Big Horn, it

was both a challenge to my Old Man to get back to work, and to see

if I could combine my own talent of "jack-knife-historian" and a

(sometimes) "realist" painter. To do something no one had done

before -- to muster the facts...and try to GET IT RIGHT...

This quest, called Here Fell Custer,

which I imagined would take about nine months took five and a

half years, and my respect for my father and others who dared to

tackle historical depictions in limited amounts of time increased

immeasurably! As a serious history painter, I can't ascribe to John

Ford's ironic dictum, "when the fact becomes legend, print the

legend." What are referred to as "Brady" photographs of the Civil

War raise some interesting points. While Brady took most of the

studio portraits, the scenes of the death and destruction, were

actually taken by his assistants, notably Timothy O'Sullivan and

Alexander Gardener. Most people when trying to sound knowledgeable

about authentic depictions of the "old west" invariably recite the

"Two R's" without realizing they were different in almost every way.

And that, of course, they had their own antecedents: Bierstadt,

Miller, Caitlin, Bodmer, etc.

Images Of Apache Raiders

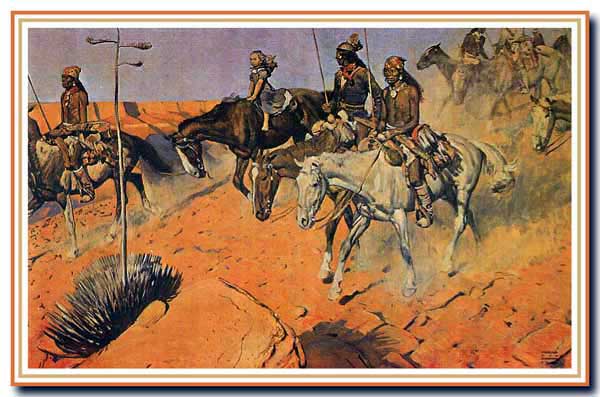

Ford, or "Pappy" as he liked to be called, (a

nice western twist on the Hemingway endearment "Papa") enjoyed the

humanizing touches my Old Man put in his illustrations. He used Von'

s image of a hostile Indian wearing a captured cavalryman's jacket

twice. Once in climactic battle in “Fort Apache”, and again

in a shot of Apaches riding with a captive child in “Rio Grande.”

But it was a perfect image that said "these guys are killers,

they've killed white soldiers...they'll do it again."

"Pappy" was an image collector. In the “captive

child" image used in “Rio Grande”, he included another telling

little detail from Von's illustration...the little girl is riding a

heavy farm horse with blinders as if it had recently been plowing in

the field. Not one in a dozen would notice these little touches, but

Ford did, and very often when he broke the rules in his cavalry

dress and gear it was for a very sound and pictorially valid reason.

The uniformity of dress was a metaphor for the

strict rigidity of a sometimes mindless military. My Old Man and

“Pappy" sometimes discussed this on the phone. Ford knew that all

those suspenders, and yellow bandanas were bogus, but didn't they

look swell in a long shot? I'm not so sure he realized that General

Crook's men on campaign actually looked more like his Welsh coal

miners in “How Green was My Valley” than what my father painted for

Bellah's Post stories.

Captive Child

artist -- Harold

von Schmidt

"The Rifleman", "Bonanza" And "Have Gun Will Travel"

But it wasn't the niceties of military dress

that would have a profound effect on both Ford and Von. It was

something else, and it would affect everything. The rapid

rise of television and the slow decline of the mass-market

magazines.

For Von it turned out to be catastrophic. His

health, never good, worsened. Fashions changed. The shrinking market

desperately sought new blood -- new faces. Von developed

diverticulosis and suffered a series of small strokes. The phone

that had stopped ringing off wall, barely rang at all.

The "magic studio" slowly became a thing of the

past.

During the mid sixties, he became sedentary. He

drank tea, ate cookies and watched a lot of his nemesis -- TV. At

night he watched “The Rifleman”, “Bonanza”, “Have Gun Will Travel.”

During the day he watched any old Western rerun he could find -- and

there were plenty. The tiny TV horses still moved with magic and

grace -- and they, blessedly didn't act.

I don't think he ever realized that he,

himself, (through John Ford and all those Saturday Evening Post

Westerns) had reinvented the Mythic West! Through their

vision, the whole pictorial west was brought to a whole new

audience, a largely unheralded accomplishment that far outstripped

Von's lifetime of honors!

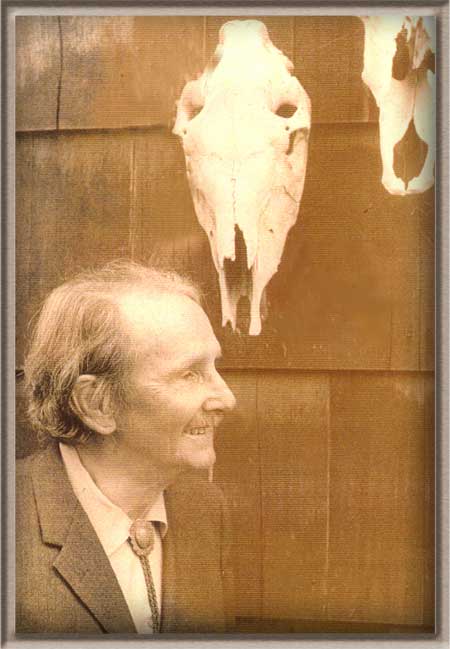

True, in 1968 he was awarded the first National

Cowboy Hall of Fame Medal, and in the early seventies two books

appeared on his western painting, The Complete Illustrator

(with the Rockwell introduction,) but sadly, his painting days

were then over.

The Images Fade

When Von was eighty-six I made a wax bust of

him that was ultimately cast in bronze. As I was working, not

surprisingly, he often fell asleep. He'd been doing it for years,

and it was mostly ignored. Finally I asked him, did he dream when he

did that? If so, what did he dream about?

He gave me a quick, chilly stare with icy eyes,

affronted by my intrusion, then glanced away, confused and

embarrassed...then said...as if expelling air…

"HORSES!"

His whole past hung in that “Rosebud” moment!

I’ll never forget that…

Norman Rockwell had perfected Americana

beyond Currier & Ivies, beyond anybody, while in roughly the same

time period Von would unleash a furious pictorial dynamic

that would ultimately bridge the gap from the printed page to John

Ford's Westerns, and on into the TV age!

If Professor Davis had done his homework and

looked at a copy of the Saturday Evening Post (as Ford had

done when he wired his partner to buy the rights to the Bellah short

story that would eventually become “Fort Apache”,) and checked out

the man who painted the pictures for the other two stories in Ford's

'Cavalry Trilogy', he would have known that Harold von Schmidt was

the link.

Perhaps if he had really connected with John

Wayne's simple premise quoted on the last page of his own book, "''Pappy' was a painter with a camera" he might have used his book to

help solve that mystery which began in the dark caves of Lascaux (there

were some horses up there too) that is still unfolding today:

why some shamans like John Ford and Harold von Schmidt still make

pictures and why people will always need them.

Back To Harold von Schmidt

(Back

to Top)

The Gallery • Painting Lewis & Clark • Vonsworks Bookstore • The Alamo • Custer • Osceola • Harold von Schmidt • Links