The Image Makers by Eric von Schmidt

Editor's Note --This chapter is from

Eric's unpublished book, Last Stands: A Sprawl of Epic Paintings

Spanning America's First Turbulent Century of Growth

The people I'll be talking about here were

trying, in their various ways, to do the same thing. TELL A GOOD

STORY WITH A PICTURE.

Four were working with paint, one was working

with film, and then there's the academic guy with the biography

thing.

The first five guys were all born before 1900.

The other guy with the typewriter was born later. I'm here to talk

about them all.

I have a problem with the academic guy,

Professor Ronald L. Davis, and his biography: JOHN FORD /

Hollywood's Old Master. (University of Oklahoma Press, '95)

which admittedly I had picked up with pleasurable anticipation.

A

Contained Fluidity...

By chance, that very spring of '95, I helped

assemble of my father's (and my own) canvases, curated by

painter and graphic designer, Howard Munce. In fact, several of

Von's had been used for the same Saturday Evening Post

stories that John Ford was later to incorporate into his "Cavalry

Trilogy" films.

The paintings we chose were a minimal

representation compared to his life-long output of well over a

thousand works, but blessedly what remained were some of the finest

-- the "family” collection. Many had been painted over the years for

now forgotten magazines like Sunset, Elks, Shriners, American,

True, Look, as well as the really big guns of the mid thirties

to mid fifties. Collier's, Cosmopolitan, and the Saturday

Evening Post were the slickest Slick of them all.

When we ended up with sixty or more paintings,

almost all oil on canvas, nearly all measuring from 24" x 30" to 36”

x 50", we began to wonder, did my father paint absurdly large, or

has our vaunted technology, our lasers, drum scanners and computers,

obliged us to paint absurdly small?

They all expressed a pictorial unity, a

poster-like clarity of meaning, a contained fluidity... and

seeing them all side by side it struck me that they all began as

tiny sketches, a scribbled pencil composition, all rendered in tone,

with no detail at all, and that in his mind translated to sky /

earth, shadow / light. For him all the rest of it was already

there -in his mind.

The Three Rs (Remington, Russell & Rockwell)

And when I read in Davis' biography (on page

187) that when in Monument Valley, shooting "My Darling Clementine",

"Ford would arrive on the set, grab his finder (an optical device

that shows the area visible through the camera's lens) and he would

be ready to go to work,” the von Schmidt/Ford connection became

clear.

Artists are a notoriously elusive bunch. John

Ford (1894 -1973) is a classic example. Now let me name some others

Davis mentions: Frederic Remington (1862 -1907), Charles Marion

Russell (1869- 1926), and some he doesn't; Harold von Schmidt (1893-

1989), and Norman Rockwell (1894 -1978).

The elusiveness of these artists was due in

part to the fact that all of them, but Remington, tended in their

work to celebrate the common man rather than Themselves -- to

glorify their lives and the work they did rather than their

own. In fact, Ford, Russell and my Old Man, professed to be little

more than “day laborers." Ford, in particular despised

“intellectuals" and academics, while Von delighted in running on the

Democratic ticket in a town that always voted republican. Charlie

Russell made a career out of poking fun at stuffed shirts and

royalty, although he and Mrs. Russell accepted all their

invitations. Rockwell was a little closer to the reality of his

abilities but was still canny enough to ask the plumber if he liked

his latest Saturday Evening Post cover. Remington, the

exception, was a bit of an east-coast snob and the only one who

seemed, toward the end, to pursue art with a capital “A ".

Actually, all of them were acutely aware of

their worth and false modesty aside, felt comfortable with the

splendid rank chosen by Colonel “Davy" Crockett, when in March of

1836, was offered the command of the defense of the Alamo and said

“no thank you. I prefer to remain a ‘High Private’”, surely the most

egalitarian rank of all...the operative word was “high”.

As Von's canvasses emerged from the cramped

stacks, they almost seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. It was like

turning back through the pages of history. Look here: a small group

of combat soldiers barely visible through a screen of jungle

foliage; look closer, you notice the bullet holes in the leaves. Now

here, a western: riders exploding toward the viewer with other

figures by an adobe building firing at them, trying to hit the

horses: everyone is absolutely terrified. Next, there is a girl in a

hoop skirt, slumped against a closed door, her eyes brimming with

tears, a crumpled letter on the floor nearby. Here: hidden Apaches

gaze down a rock out-cropping at a wagon train far below. A warrior

kneels on the back of his pony to get a better look...he is wearing

a cap decorated with the feathers of an owl...he is a watcher...

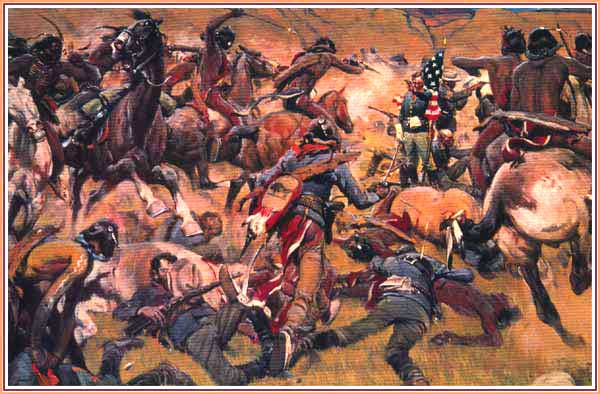

...bullet

holes in the leaves

artist -- Harold

von Schmidt

The

Fetterman Massacre

While peeling back the layers of history and

viewing these huge paintings, one after the other, each canvas as

fresh and vibrant as if it had come off the easel yesterday, we

realized that the limitation of the gallery space would not present

a problem. These paintings, so tautly constructed, each so powerful

individually, they could almost be hung frame-to-frame. Indeed, they

could even be "stacked," one above the other. Each had a startling

immediacy and could hold its own!

Lots of "Von" stories got told over the course

of that exhibition. And "Jack" Ford Stories, too. Seeing some of

those cavalry paintings reminded me that Von was Ford's favorite

living western illustrator and how he used Von's compositions in his

westerns shot in Monument Valley.

But you certainly wouldn't know it by reading

Davis' book about John Ford.

I was in high school at the time, and posed for

almost all the pictures (both as Indians and the cavalry), and I can

attest how proud the family was of the "Jack/Von" Mutual Admiration

Society. We were as delighted to see Ford's recreation of the Old

Man's compositions in his cavalry films as when they first appeared

as double page spreads in the Saturday Evening Post.

Davis does underline the Saturday Evening

Post connection when he mentions that the film, "Fort Apache"

was based on James Warner Bellah's short story "Massacre”. "Ford

read the story aboard the 'Lurline' on his way to Hawaii. He told

his daughter to wire Merian Cooper, (his partner) to buy the movie

rights." Davis then goes on to say that the film became Ford's

version of the Custer Legend. While this is probably true, Bellah

actually used for his story incidents that related to a different

battle, the "Fetterman Massacre”, which happened near Fort Phil

Kearny in the winter of 1866. However with a name like "Fetterman"

your chances of ending up a legend in American history are about

zip.

Ford used historical fact when it suited his

purpose. Bellah had used Sioux and Cheyenne as the attackers in the

Massacre (which was correct for either the Fetterman or the Custer

Massacre) Ford, on the other hand, used real Navajo and had them

dress up to look like Apache -- historically incorrect on

both accounts!

Fetterman

Massacre

artist -- Harold

von Schmidt

Eric Meets "The Duke"

The von Schmidt/Ford connection thickened later

that summer. After I had posed for all those "shape-shifting"

warriors, I was dispatched to a camp in Durango, Colorado, called

the "Explorer's Camp." I was not thrilled about going but it did

have its moments. One of those was a visit to Monument Valley where

a film company was making a movie. The movie was called "Fort

Apache".

We arrived at night by truck, and I doubt if

Ford was there, but I do remember meeting John Wayne. He was huge.

My hand disappeared into his and he said... "Your Old Man? He

painted the pictures for this? That's Great, Kid!" I was too dazed

to say "yeah, and I posed for them!" I was, in fact, speechless.

Maybe John Wayne didn't know the name of the

guy, who had done those pictures, but he knew the pictures. Ford

knew those pictures too, and he knew the guy who painted them!

Davis, unfortunately, did not. What we find in

the biography, are numerous references to Russell and Remington,

what one writer has called the Tweedle-di and Tweedle-dum of Western

Art. Unlike Captain Fetterman, their splendidly alliterative names

trip lightly off the tongues of those who couldn't tell a Bodmer for

a Bierstadt. And while they embodied totally different approaches,

they seem to be forever joined-at-the-hip, as if Charlie had gone to

Yale Art School with Frederic, and Remington had been a night-herder

with Russell.

The Image Makers Page 2

(Back

to Top)

The Gallery • Painting Lewis & Clark • Vonsworks Bookstore • The Alamo • Custer • Osceola • Harold von Schmidt • Links